The loud beeping from the monitor pierces the room. The patient's heart rate is accelerating, his breathing is labored, and he is starting to cough. Also, the right side of his face is swollen.

(Published: December 2016)

"Do you have any allergies, Mr. Schönfeld?" the physician asks, bending over and carefully feeling around the patient’s neck. "No allergies," comes the reply, in a slurred voice. But with the patient’s blood pressure dropping rapidly, Nurse Romy Wiessner asks if support should be called in. At a nod from Assistant Physician Dr. Roland Hiersemann she rushes to the telephone, and calls into the handset: "We need backup in the emergency department!”

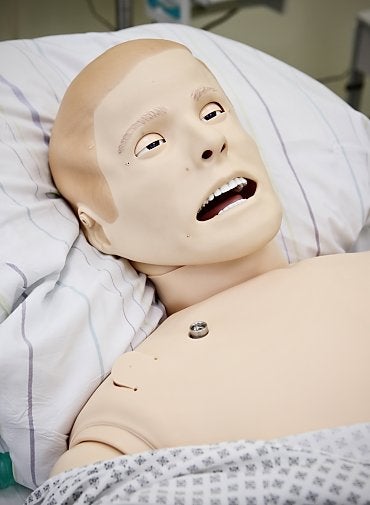

Wiessner, on returning to the patient's bedside, rolls up his sleeves and inserts an IV cannula. When she withdraws the needle there is a drop of blood on it. Usually, this would be unremarkable, but in this case it is technical ingenuity: Mr. Schönfeld is not made of flesh and blood, after all, but of plastic, wires and electronic components.

In the Simulation Center at HELIOS Hospital Hildesheim in northern Germany, doctors and nursing staff train not on real patients but on high-tech patient simulators – mannequins such as Mr. Schönfeld that look like patients and can talk, breathe and perspire. They have a pulse, and you can take blood samples from them. Sometimes they even cry.

That they react like real patients is in no small part due to Stephan Düsterwald, the center’s medical director, and his team. During each training session they huddle in a small room behind a glass panel and control the patient simulator’s reactions – making the heart beat faster or the eyes blink, for example. "We can simulate life-threatening situations in a realistic environment without harming a patient,” Düsterwald explains. “In these stressful situations here, unlike in real life, mistakes are expressly allowed."

"A little while ago it was only a piece of plastic, but just now it was my patient."

Just as the second team of doctors, headed by Dr. Martin Köhler, arrives, the oxygen level in the blood of the “patient” drops sharply: He is in critical condition. Dr. Hiersemann calls out to check that adrenaline has been given, as ordered, and looks around the room, but no one answers. The other team members busily fetch drugs, attach oxygen and measure blood pressure again, while continually glancing up at the monitor. Still there is no improvement, so the doctors quickly administer an anesthetic and begin an intubation – which proves to be difficult because of the extreme swelling of the throat. As Dr. Köhler carefully inserts the breathing tube into the windpipe, Dr. Hiersemann sets his stethoscope on the patient simulator’s plastic chest, and after a few seconds confirms the tube is in the correct position. The mechanical ventilation is started and the treatment team looks relieved as the blood’s oxygen level starts to increase.

Suddenly, the beeping of the monitoring screen stops and there is silence. Düsterwald and his team enter the room, ending the 15-minute training session. Slowly, the participants start to relax. "It felt completely real," Dr. Köhler says in a tone of near-disbelief, as he instinctively goes to a dispenser and rubs some disinfectant into his hands. "A little while ago it was only a piece of plastic, but just now it was my patient."

Everyone makes mistakes: Every 30 minutes on average when performing routine duties, and much more frequently – as often as twice a minute, according to studies – during more complex, higher-stress tasks.

“Professionals also make mistakes,” says Düsterwald. “We record all the training sessions with a digital audio video system, which enables us to detect even slight irregularities and analyze with the participants how they could have been avoided. And this way we ultimately improve the safety of our patients. Our doctors and nursing staff can draw on a vast wealth of knowledge and experience, and even in the most serious situations the knowledge needed to solve the problem is often in the room. We just need to make sure the right measures are actually carried out on the patient. Communication within the team and with the patient plays an important role, so that is something we focus on during the training sessions."

Afterward, the participants gather for a debriefing and to view a few key scenes from the video. Enough time has passed for them to watch with a good measure of objectivity, and they not only congratulate each other on successful diagnoses but are able to openly make some constructive criticisms. "The handover to the second team of doctors could have been more coordinated," says Bastian Overheu, the Simulation Center’s deputy director. "It was no longer clear who was leading the team. A short break, using the 10-for-10 principle for example, and the situation could have been straightened out."

According to this principle, doctors and nurses should continue to take short breaks – especially when things are hectic – even for as little as 10 seconds every 10 minutes. That is enough time for the physician in charge to announce the treatment plan out loud, ensuring that everyone on the team has the same understanding of the situation, and to ensure that good ideas from the nursing staff do not go unheard.

“Good teams often have, implicitly, the same understanding of a situation,” explains Düsterwald. “They communicate almost without words. Misunderstandings are rare, but they can occur, so it is always good to let colleagues know that you have heard questions or instructions. That is a simple and important safety mechanism that we pass on to all our participants.”

At Fresenius Helios, simulation training for all doctors and nursing staff in higher risk areas, such as intensive care medicine and anesthesia, became mandatory this year. Specialists from emergency medicine, obstetrics and the cardiac catheterization lab undergo regular training. Other concepts are planned for gastroenterology and surgery. All participants take courses conforming to unified standards, and in fully equipped operating and treatment rooms.

More than 600 separate training days are held annually in HELIOS’s simulation centers in Hildesheim and two other German cities, Erfurt and Krefeld. The company has invested a total of about €2 million in the three facilities. A special feature of the Simulation Center in Krefeld is a fully integrated simulation ambulance: to make it as realistic as possible, the “vehicle” has the full original interior and even comes complete with rear and side doors.

Contact

Helios Kliniken GmbH

Friedrichstr. 136

10117 Berlin

Germany

T +49 30 521 321-0